Pest porfolio #1: How do feral cats threaten Australian wildlife?

Australia has always been a land of extremes: vegetation quick to ignite at the first dry breeze, and rivers that swell with the wet season only to vanish into hiding for months.

And yet, many of our native species have adapted; against all odds, the amphibians, the mammals, the birds and quiet little reptiles have carved out a way to survive and thrive for thousands of years. That balance held until recently, when threats emerged that Australia’s native fauna could never have anticipated: settler-introduced pests, better known as invasive species.

One such threat is feral cats.

Now covering 99.8 per cent of Australia’s mainland and island territories, feral cats are responsible for devastating losses to wildlife. Statistics paint a grim picture, while on-the-ground observations illuminate how far and widespread this issue has become for conservation efforts.

In the face of unprecedented population decline for native species, feral cats are certainly executors of extinction. Let’s take a closer look at their pest portfolio to flesh out how the problem grew, the damage they cause, and the solutions available to us.

The first paws that stepped ashore

According to the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, cats colonised the nation as early as 1788, coming ashore with the first fleet. Genetic analyses and historical data indicate cats had spread across the entire continent within 70 years, with only 0.1 per cent of land mass remaining cat-free today [exclusively on islands or purposefully fenced and protected areas]. This surge was fueled by later introductions to manage other non-native pests, especially those which created complications for farming. Unfortunately, cats found a thirst for more than just rodents and rabbits.

A collation of almost 100 studies indicates there are now approximately 3.8 million domesticated cats in Australia, and anywhere between 2.1 and 6.3 million ferals: a figure which fluctuates with rainfall and availability of prey.

Though most people make a distinction between pet cats and ferals, it’s important to note they’re the exact same species and possess an equal capacity for predating on wildlife.

Forget the millions, loss is in the billions

What matters even more than the headcount is the havoc they wreak — each pawprint carries consequences far beyond cat numbers.

Gulf Savannah Biodiversity Officer Dr Edward Evans explains why cats pose such an outsized threat to native species compared to other predators.

“Cats are very elusive and hard to monitor, they’re hard to trap and track,” he said. “Australian wildlife has evolved without cats in their environment, so they don’t recognise cats as a threat.”

This concept, scientifically referred to as ‘prey naiveté’, accounts for the fact that native species lack evolutionary predator recognition for certain dangers. For example, studies suggest the impact of feral dogs and foxes is less significant due to their taxonomic connections: native species have had approximately 4000 years since canids, in the form of dingoes, were first introduced. Hence, they’ve had time to develop the typical responses for staying safe: camouflage, mimicry, flee, hide, and at all costs – avoid.

When it comes to felids, these anti-predation instincts are still catching up. Though scientists believe wildlife will eventually wisen to cats, the question is whether their declining populations have time for evolution to correct their behaviour. Statistics indicate they do not.

“There are many small to medium-sized mammals that have gone extinct either directly or in part due to feral cats,” Dr Evans said.

Though there are many ways to illustrate this devastating knock to wildlife, it is difficult to capture the full scope and impact. Cats have played a major role in the extinction of 25 native species, including the lesser ‘yallara’ bilby, pig-footed bandicoot and broad-faced potoroo.

Cats continue to be a major concern for land mammals such as the bilby, bandicoot, bettong and numbat. In fact, predation by cats is a recognised threat to over 200 nationally threatened species, and 37 listed migratory species.

A single roaming, hunting cat will kill more than three animals every week, which adds up to approximately 186 animals per year.

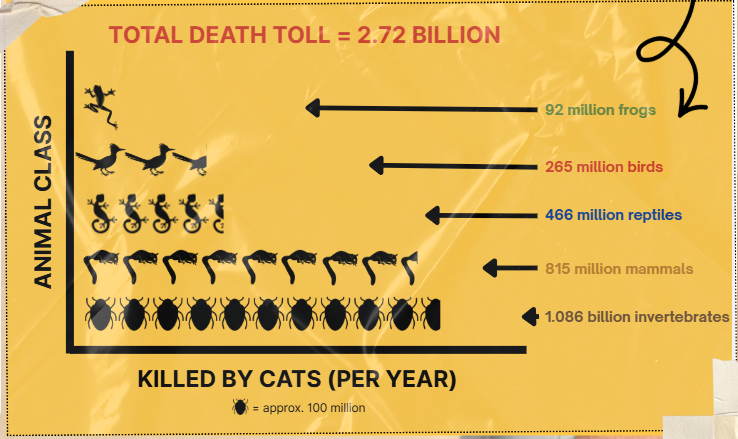

This leads us to the truly concerning figures. Each year, across Australia, feral cats kill:

And of course, as is the case for any ecosystem, if one species disappears, flow-on effects follow and leave long-lasting impacts we cannot at this stage be certain of.

No simple solution

When it comes to controlling cats, there is no quick fix, especially when they have an uncanny ability to win over human affection: scientists even suggest their parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, may play a role in positively influencing human behaviour towards cats. This emotional pull complicates any effort to reduce their numbers, even as evidence mounts of the damage they cause.

Dr Evans even confesses:

“I like cats – they’re cool animals and amazing predators, but unfortunately they’re a huge issue for native wildlife.”

Across Australia, management measures are debated and range from tighter laws for pet owners, to targeted shooting programs, to one north-Queensland shire that even offers a $10 bounty for cat scalps. Each method sparks controversy: what’s humane, what’s effective, and who decides?

On the ground, Gulf Savannah NRM is trialing practical solutions of its own, including the deployment of motion-sensor camera traps in Mt Lewis National Park and Mareeba Wetlands Reserve.

Biodiversity Officer Océane Dupont explains the initiative in more detail:

“By setting up these cameras, we’re trying to protect the broader ecosystem,” she said. “We’re trying to see what the status of the native species is, such as the northern bettong, and get a feel for the threats they’re facing.”

Each camera is a small but vital step toward understanding what’s happening on the ground. By gathering clear evidence of threats and species activity, projects like this give communities and decision-makers the information they need to undertake cat control methods moving forward.

The challenge, as GSNRM staff will tell you, isn’t just removing a single predator: it’s balancing science, culture, and community values to give native wildlife a chance to recover.